Written by Fola Yahaya

If you’ve used Apple, Google or Microsoft products recently, you’ll have noticed how AI is becoming the default for so many tasks – whether it’s auto-suggesting your email reply, automatically editing photos or summarising your meetings. AI is creeping into our daily interactions, often without us consciously choosing it. Desperate for profit, Big Tech is increasingly making ‘AI-powered’ the default, rather than letting us decide if we want it.

The downsides of this are significant. First, it assumes that AI is always the best solution, which most of the time it clearly isn’t. More often than not, we need to think through a problem ourselves or experience the process of creating without shortcuts. AI-first ‘creativity’ erodes the joy (and pain) of the blank page: the unique satisfaction of starting from scratch and seeing where your thoughts and creativity take you. It’s in the struggle to create that innovation often happens – whether you’re drafting an article, designing something new or tackling a complex problem.

Secondly, we need to consider privacy. I’m old enough to remember a time when an individual could be truly ‘unknown’ and live off-grid. This is no longer possible. We gladly give up our data – our likes, dislikes, fears and dreams – in exchange for social credit or access to a shiny new piece of tech. In so doing, we are like turkeys voting for Thanksgiving: willingly enabling AI systems to undermine, learn from and ultimately use our uniqueness against us.

So, we should all be pushing for an AI opt-out which will allow us to have some control over our digital lives. We should have the choice to decide when and where AI gets involved, especially in tasks where we want to retain our own creativity, privacy and problem-solving abilities. As useful as AI is, making it the default removes the element of choice – and that’s something we must all fight against.

I’ve got back into podcasts and, stuck in a car for a few hours, downloaded a really interesting episode featuring Yuval Noah Harari, the best-selling author of Sapiens. Long book short, his main thesis is that successive information technology waves – from people writing stuff with muddy sticks to the Internet –, rather than empowering us all, have actually enabled the weaponisation of information dissemination.

Take, for example, the invention of the printing press. In 1543, Copernicus’ groundbreaking book debunking the myth that the Sun rotated around the Earth sold a paltry 500 copies. Conversely, what people bought in droves were small, scandalous pamphlets about salacious topics like Satan-worshipping, penis-stealing witches. Ok, so linking what people want to read (salacious gossip) with the Spanish Inquisition is an incredibly weak argument, however, his main point has some merit.

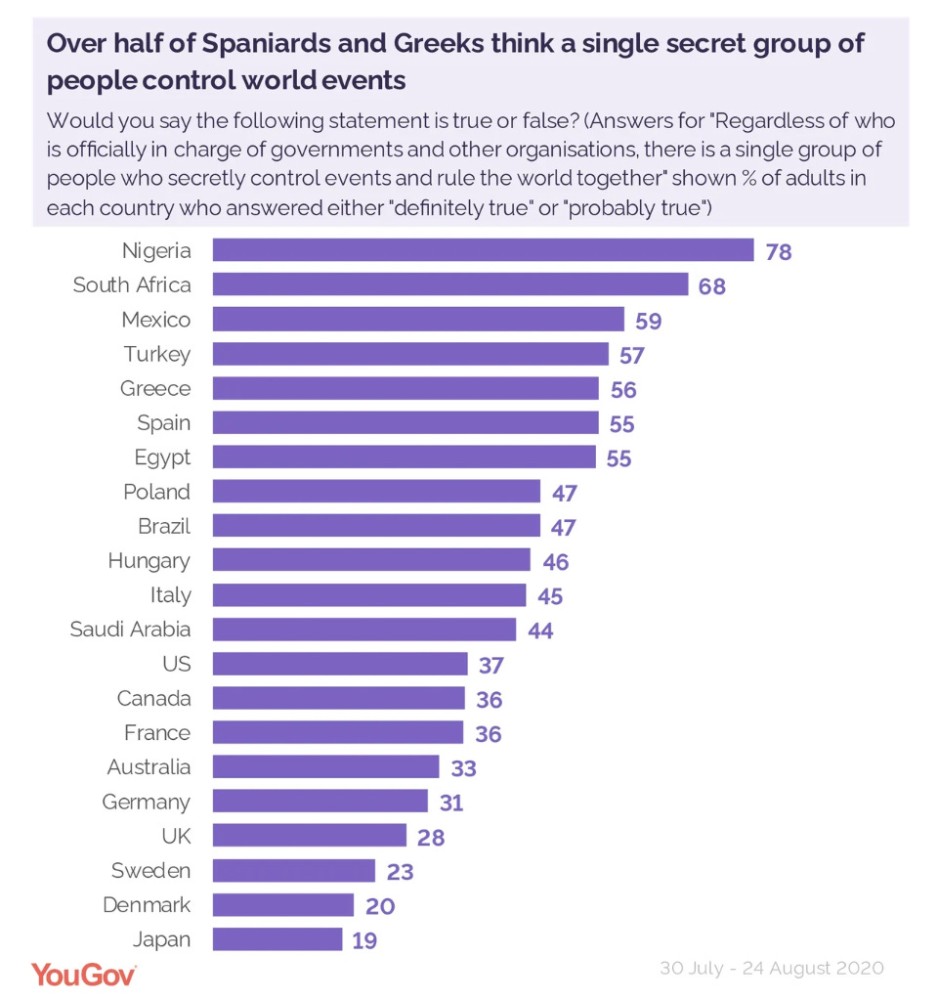

That while in theory these seismic improvements in information accessibility make us smarter, in the immortal words of Dorothy Parker, you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink. Despite today’s unparalleled access to knowledge, most people waste their time scrolling through Instagram, and being manipulated by algorithms that will soon know us better than we know ourselves. As Harari says, “If humans are so smart, then why are we so stupid?” (see the infographic below about the global level of belief in ‘Illuminati-like’ overlords (my fellow Nigerians… seriously?!)).

Harari goes on to argue that these algorithms, combined with the slow and steady march towards 24/7 surveillance, mean that all of our worlds are/will soon be filtered through the lens of AI-generated echo chambers that will fracture society. Critically, that in a world where everyone has their own curated version of the truth, finding common ground will become almost impossible.

Watch the video interview and listen to one of the smartest cookies on the downsides of AI. What I like about Harari, sensationalism aside, is that he is a proponent of a few practical steps that regulators should be taking:

The massive elephant in the room is that, in their desperation to not ‘fall behind’ in the AI race, governments are falling over themselves to keep Big Tech happy. Simply put, few have the cojones to take on Big Tech. I fear that we’re trying to close the gate after the horse has already bolted.

OpenAI has rolled out Advanced Voice Mode (AVM) for ChatGPT. Initially demoed last summer with, controversially, a voice that sounded suspiciously like Scarlett Johansson, AVM is finally available in most Western countries, and this update is a game changer on several levels. Firstly, it finally promises a useful Siri/Alexa/Google assistant, and transforms AI from being an impersonal tool manipulated via a screen to an intimate tool masquerading as whatever you want it to be.

Weirdly, just adding a real-time voice that you can interrupt enables AI to play a whole raft of human roles. From being your lover to your therapist (and critically combined with its default memorisation of previous conversations), ChatGPT has now been unshackled from the constraints of the prompt box and will soon be the de facto user interface in every digital app.

The genius of OpenAI is that, as the owner of the most powerful AI assistant, it now gets:

Currently limited to just a handful of annoying American voices (though you can customise it to speak in whatever language or accent you wish), it enables myriad use cases such as being a fully fledged, very patient personal tutor. You can access it via the paid-for ChatGPT app and, though it has ridiculous limits, is heavily censored and sometimes struggles to understand your input if there’s background noise, it is incredibly powerful.

If recent history has taught us anything, it’s to be sceptical of AI and augmented reality (AR) hardware. I made a video about the very expensive r1 AI device paperweight that I succumbed to six months ago and now, news comes of Microsoft’s decision to shut down its much-hyped HoloLens AR headset. Despite years of development and lofty promises, HoloLens was a fundamentally flawed concept. It made people sick, was clunky and, with a price tag of $3,500, was never going to be a mass market product.

The same could be said for Meta’s latest AR push with the Orion glasses (built in collaboration with Ray-Ban). Zuckerberg’s vision of the future is impressive on paper – immersive digital overlays seamlessly blending with the real world – but there’s a big question: Why would anyone need it?

The reality is that these devices are expensive and often impractical. VR headsets have been around for years, but they’ve never truly become mainstream. Why? Because people like talking to each other face-to-face, without a headset or glasses in the way. AR hardware feels like a solution in search of a problem. Sure, it’s flashy, but the utility just isn’t there for most people yet.

Network Hub, 300 Kensal Road, London, W10 5BE, UK

We deliver comprehensive communications strategies that deliver on your organisation’s objectives. Sign up to our newsletter to see the highlights once a quarter.