This month, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, is the subject of our series investigating the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) for achieving the SDGs.

Written by Amy Chaplin

Education is fundamental for children and adults across the world, and is imperative for employment and development. Despite this, we are facing an education crisis: 244 million primary school children are not attending school, there is a chronic lack of qualified teachers, and government investment in education policy is diminishing.

To overcome these failings, artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being touted as a potential solution, with teachers already using it to help speed up marking and lesson planning. AI is also being incorporated into vocational training and used to collate data on school connectivity.

While AI can help plug gaps in educational attainment, it won’t solve the very human problems of poor teacher remuneration and limited education investment. There is also the elephant in the room of inadequate electricity and connectivity.

These caveats aside, AI can have (and is already having) positive impacts in widening access to education. Moreover, it will clearly introduce a new paradigm for how education will be delivered. Given this backdrop, our article will explore how AI is being used to aid development.

©SmartEdge/World Bank, Students participate in an AI after-school program in Edo, Nigeria

There have been significant efforts in the developing world to leverage AI to make teachers’ jobs easier, with mixed results.

Kenya in particular is becoming an epicentre for AI innovation in education, with companies like Kytabu developing AI-powered tools designed specifically for the African educational system. Kytabu’s M-Shule product is an edtech platform that uses AI and SMS technology to deliver personalised learning content to Kenyan primary school students, improving education outcomes in areas with limited internet access (albeit 38 out of 47 Kenyan counties found that most teachers lacked the AI literacy to effectively use the tools on offer).

In Nigeria, an increasing number of teachers are using AI to assess children’s literacy levels and understand where they are struggling. Again, this comes against a backdrop of a fragmented education system. As is customary, this year, primary, secondary and tertiary teachers in Nigeria have been striking as a result of low pay, poor working conditions, overcrowded classrooms and lack of professional recognition. This has led to wide-scale closure of schools and universities for up to six months at a time. So, while momentous advances are being made in edtech, the government first needs to address the myriad of problems within the profession.

AI is increasingly being used to analyse data and automate certain tasks in a range of vocations. According to the World Economic Forum’s The Future of Jobs Report 2020, the shift to AI will create 97 million new roles in training machines. An education in AI is becoming crucial for the world’s future workforce.

For example, educational institutions like Des Moines Area Community College in Iowa are creating AI training courses that provide students with the skills to effectively use AI in the workplace. Microsoft is also expanding its UK skilling programme, Get On, aiming to equip 1 million people with the skills required to thrive in the AI economy.

Nevertheless, AI training courses require significant investment from governments. While the British, American, Chinese, Indian, Malaysian and Chinese Governments are investing billions in AI skills programmes, only six countries in the Latin America and Caribbean Region have even formulated specific strategies on AI or agendas for AI promotion. This illustrates AI’s potential to deepen skills inequalities across nations.

© John Brecher, How a small city in Iowa became an epicentre for advancing AI

Giga, created by the International Telecommunication Union and the United Nations Children’s Fund, is harnessing AI to narrow the digital gap between the Global North and the Global South. This initiative uses AI to analyse global satellite imagery and map schools’ connectivity in real time, with the goal of providing leaders with the data to make decisions on connectivity procurement.

© UNICEF Giga, Giga Map Launch

Giga Maps aims to inform decision-making about internet procurement. The initiative has seen positive uptake: for example, Vlatko Drmic, Deputy Minister at Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Ministry of Communications and Transport, said his country would employ Giga Maps to help “negotiate better prices for Internet packages for schools”. Giga’s work has had an impact in a further 34 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

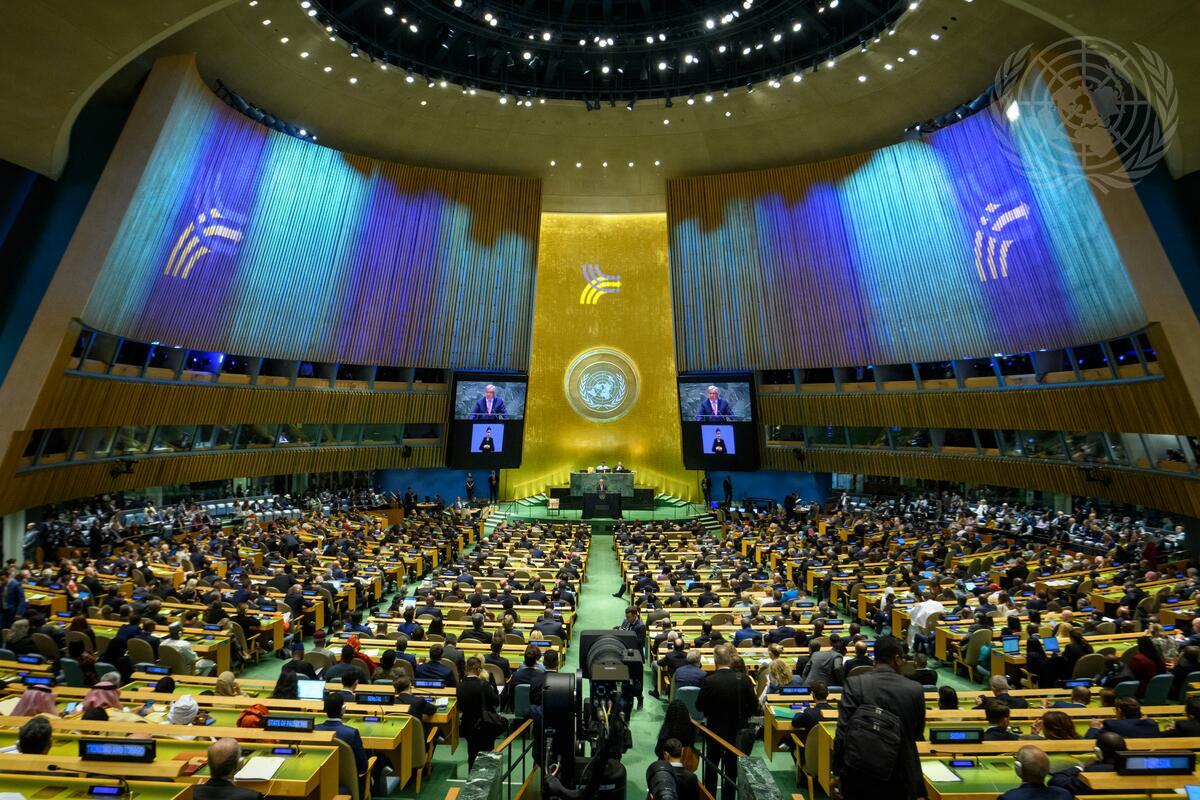

The importance of Giga’s work to development has been marked by its recognition in the United Nations Global Digital Compact. Although a step in the right direction for AI regulation, critics are sceptical as the compact is non-binding. With 1.3 million children currently attending schools without Wi-Fi, there needs to be more urgency in the international community to enshrine edtech in policy.

© Frank Franklin, UN’s Global Digital Compact

Like the internet, AI can provide a raft of innovative solutions in education. AI will not however solve the all-too-human problems that lie at the heart of educating the world’s children.

AI is unrivalled in certain situations, especially for assisting and upskilling teachers and analysing student data. For developing countries to make the most of the edtech on offer, governments need to come up with robust plans to support teachers to implement it.

Where there are complex humanitarian situations, simply keeping schools open is the most pressing challenge.

Supporting equitable, quality education for all calls for more than AI innovations – it demands a vast rethink of the value of education and multilateral investment in it.

Do you work in the development sector on a project that uses AI to achieve the SDGs? If so, we’d love to hear from you.

Network Hub, 300 Kensal Road, London, W10 5BE, UK

We deliver comprehensive communications strategies that deliver on your organisation’s objectives. Sign up to our newsletter to see the highlights once a quarter.